|

|

|

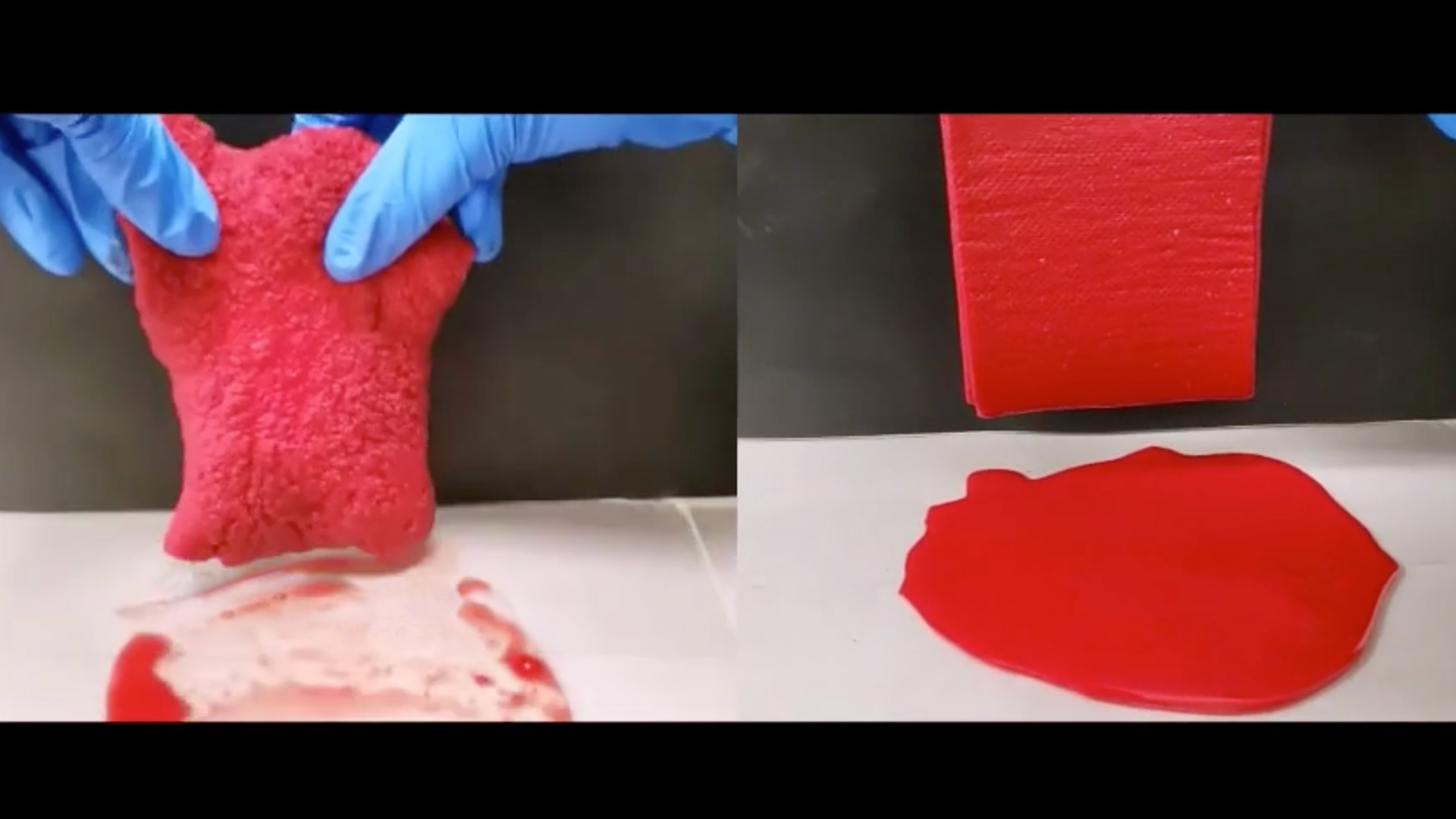

UMD researchers used a hydrogel sheet (left) to absorb about three times more water-based liquid than materials like gauze. Image by Matter/Choudhary et al. |

|

It’s paper towels to the rescue for soda spills and tomato sauce splatters in the kitchen, while gauze often soaks up blood in the operating room. But Maryland Engineering researchers have created a better picker-upper by using a hydrogel—a gelatin-like material in the form of a dry sheet—that absorbs and holds about three times more water-based liquid.

The method, presented recently in the journal Matter, produces an absorbent, foldable, and cuttable “gel sheet” that may one day find a home in kitchens, bathrooms, or medical settings. Unlike typical hydrogels, which are made of a web of large molecules known as polymer that soak up more than 100 times their weight in water, the new material does not become brittle and crumble when dry.

“We reimagined what a hydrogel can look like,” said corresponding author Srinivasa Raghavan, a UMD professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering. “What we’ve done is combine the desired properties of a paper towel and a hydrogel.”

To craft the gel sheets, the research team mixed acid, base, and other kinds of ingredients for the hydrogel in a zip-top bag. Like vinegar meeting baking soda, the mixture released carbon dioxide bubbles within the gel, creating a porous and foam-like material. Next, the zip-top bag was sandwiched between glass slabs to form a sheet and then exposed to UV light, which sets the liquid around the bubbles, leaving pores behind. Lastly, the team dipped the set sheet in alcohol and glycerol and air-dried it. This enabled the dried gel sheet to remain soft and flexible, similar to a fabric’s texture.

“To our knowledge, this is the first hydrogel that has been reported to have such tactile and mechanical properties,” Raghavan said. The gel sheets also stayed soft and flexible in ambient conditions for a year, indicating stability. “We are trying to achieve some unique properties with simple starting materials.”

When researchers placed the gel sheet over 25 milliliters (0.8 ounce) of spilled water, the sheet swelled and soaked it up within 20 seconds, holding the water without dripping. However, the cloth pad only absorbed about 60% of the water, leaving drips behind.

The gel sheet also performed well with thick liquids, such as syrup, blood, and even fluids that are a million times thicker than water. The researchers found that the gel sheet could absorb nearly 40 milliliters (1.4 ounces) of blood within 60 seconds, while gauze dressing soaked up only 55% of the blood. The gel sheet also holds its liquid well, whereas the blood-soaked gauze trickles.

Compared to sanitary pads, sponges, and gauze, the gel sheet absorbed over two times more blood than the others.

Next, the team plans to optimize their gel sheets by increasing absorbency, strengthening the material, lowering the cost, and making the sheets reusable. The researchers are also looking to develop gel sheets for absorbing oil.

Because of their flexible and absorbent nature, gel sheets also have the potential to stop bleeding from severe wounds as dressing.

“I’m always interested in taking our inventions further than just publishing a paper,” Raghavan said. “It would be wonderful to take it to actual practical use.”

In The News:

This article, which first appeared in Maryland Today, was adapted from a release by Cell Press.

January 12, 2023

|